In May I received official message that I had been awarded the status of Excellent Teaching Practitioner with four colleagues from BI.

To cite an official description: “The excellent teaching practitioner (ETP) status is granted based upon proven merit and commitment to teaching and educational excellence. The ETP is independent of other academic promotion schemes, and the title ETP can only be awarded to people who develop their teaching competences systematically and over time to a level that is significantly higher than the required basic competence at Universities.” The program has existed at other schools for a few years, but this is the first year BI awards it.

I thought I would use this space to reflect a bit on the whys and hows of this status change – as well as the process, to encourage more of my colleagues to seek it.

Why apply for ETP?

I have always cared about the teaching part of the job, partly because I am better at that than publications, partly because I think quality in teaching is an important differentiator for higher education institutions in general and business school in particular. We need good teaching. BI, a private institution competing with practically gratis public institutions, need it more than ever.

While focusing on teaching is great for your life quality and sense of purpose, it is a killer in terms of more material rewards. You will not get promoted to full professor by being a good teacher and publishing on teaching (at least not in Norway: My excellent colleague Bill Schiano was promoted to full professor at Bentley in 2015 in no small measure because of the book we wrote together.) Good teaching will be rewarded with nice words and rather quickly evaporating brownie points, illiquid outside your own institution. Unless you shift over to becoming a professor of pedagogy (i.e., change careers) you will have to take your rewards intrinsically (happy students and good experiences in the classroom) or outside the institution (consulting, speaking, board memberships etc.).

Prestige?

Apparently (and I can’t find the quote, ChatGPT or not) a cantankerous old editor of The Times disallowed the word “famous” when describing someone. The reason was that if the person was famous, the word was unnecessary – and if not, incorrect.

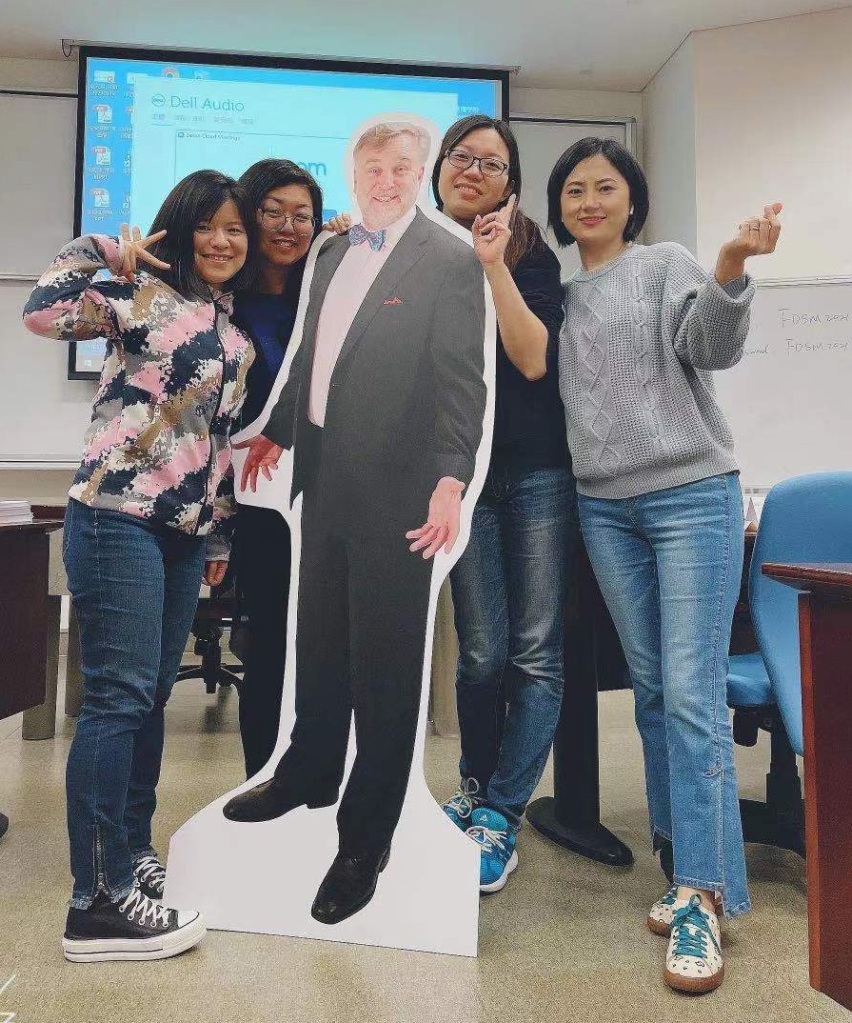

So I am a little puzzled that the ETP is referred to as “prestigious” in the announcement. However, some really good teachers, such as my friend Arne Krokan at NTNU, has been awarded it (he was one reason I applied, actually). And I certainly feel proud when my photo appears next to my colleagues above. That is prestigious, at least to me.

The ETP status, however, carries some tangible benefits aside from whatever prestige it may confer: A (modest) salary increase, permanent and applicable towards your pension. While the sum is not large, it is high enough that it makes the process of applying worth doing in itself. (The salary increase certainly does not pay for the extra effort you have put into your teaching over the years, but it is not intended to.)

A second, and perhaps more important consideration is that the pendulum in academia has swung very far out on the research & publication end, and is now coming back towards teaching & relevance, particularly for business schools. The ETP status is something implemented by the government and adopted by BI to shift focus towards quality in teaching – and if nobody applies for it, it loses value.

So, dear colleagues with excellent experience with innovative teaching – yes, I am looking at you Ragnvald, Øystein, Hanno, Anna, Pål, Robert and doubtless many others – do go ahead and apply!

That will increase my prestige!

And now for the process:

The application itself

To help people apply for ETP, BI has created an internal web page and sought the help of a consultant (Prof. Trine Fossland) to advise applicants. I had two video sessions with Trine, and she helped me structure my application. The application is quite comprehensive, and it is good advice to take out as much of your documented experience as possible (that goes into the pedagogical CV, which, if you have not created it gradually over the years, is quite a bit of work in itself.)

Writing an application is an exercise in focus: You need to show that you fulfil the criteria, that the evolution and innovation you have done is a planned activity, consciously undertaken, and that you can credibly claim to want to continue it. You need to pick a few activities and show their change over time.

For me this was difficult – I have never had a plan with what I do, but a constant dissatisfaction with my courses (I really should do better) and an appetite for new technology and new ways of doing things has helped me maintain an innovative pressure. I try to explain that I put a lot of work into my courses because I am inherently lazy and want to work as efficiently as possible, but that excuse is wearing a bit thin.

Innovation comes from trying things at the edge. I have always been someone who wants to try things out, often by “breaking” rules or at least tradition – such as currently teaching a course at UiO and BI at the same time, mixing the students. The students love it (and have asked med to force cross-institutional teams the next time I teach it), the administration at the operative level are helpful, but you do run into a lot of “this is how we do it here” issues, often expressed as pedagogical principles that as a rule are neither pedagogical nor principled.

At some point I really need to write that “Innovators are irritating” paper I have been thinking about for so long…

Pedagogical course requirement

Midway through the process (actually, after the application was submitted) I discovered that one of the criteria was that I had to have the basic education course (Utdanningsfaglig kompetanse) that all newly hired faculty at BI must take. That was kind of a bummer and in my view an unnecessary formality: I have learned and taught pedagogy at HBS and many other places around the world and taught classes since 1983. Luckily, there was an option for highly experienced faculty to basically take a home exam based on the curriculum in the course, which duly did. This required writing and submitting a teaching portfolio – a mix of a short pedagogical CV, as well as a short paper reflecting on your teaching as seen through the curriculum of the course.

Initially I saw this basic pedagogy exercise as an irritant (and, to be honest, slightly humiliating), but looking back on it, I cannot say it was a totally useless endeavor. The Learning Center (Inger Carin, in my case), was very helpful. It acquainted me with some literature – and language – of pedagogy. I found that what I had been doing over the years was recommended by the pedagogues, though it must be said that pedagogy professors never use one sentence when a few chapters or a whole book can be written instead.

In the end, it allowed me with some justification to say that what I do is grounded in theory, though I discovered at least some of the theory after a couple of decades of teaching…

The panel interview

The final stage of the process was an interview by a committee of assessors (professors from other institutions in Norway, all of them ETPs in their own right). I have not done many job interviews and have not done well in any of them, but apparently I passed well enough, and the report afterwards was very complimentary.

One thing I do remember was that my main teaching approach – HBS-style case teaching, where the students are supposed to do the talking and every class is a case-based class, with participation grading, fixed seating and other features – was not something the committee was familiar with (or maybe they were, and just wanted me to explain it.) I also got the feeling that the committee was not very familiar with executive teaching in a business school context.

My main advice to those of you wanting to go through the same process is to not take any knowledge about what you do for granted, but explain it and put it into a context. I did the usual smart thing and tried to check out the backgrounds and pedagogical focus of the committee members, but still managed to miss the mark a bit. However, they were friendly and pulled me back on track.

In conclusion

Well, there you go: A worthwhile exercise to go through to get some tangible rewards for doing the thing you love and would do anyway. Now it remains to see if this exalted status will bring reputational immortality or exciting new opportunities…

Together with Chandler Johnson and Alessandra Luzzi, I currently teach a course called

Together with Chandler Johnson and Alessandra Luzzi, I currently teach a course called

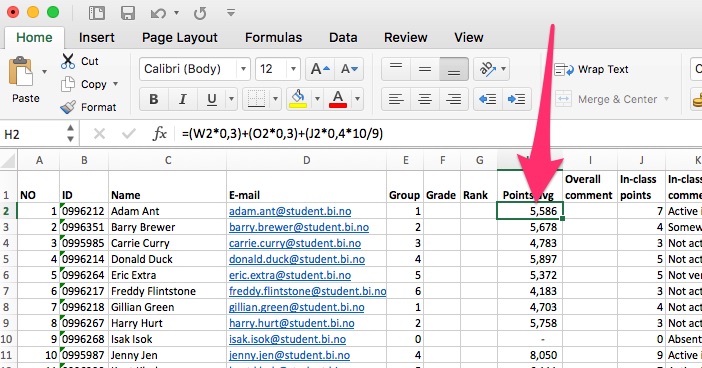

I have just finished teaching four days of data analytics – proper programming and data collection. We (

I have just finished teaching four days of data analytics – proper programming and data collection. We ( I just got the message that the new bachelor program

I just got the message that the new bachelor program

This is just about the 15th time I teach in China, all of it in cooperation with Fudan University, which gives me some cause to reflect on how teaching in China has changed – all seen from my rather narrow perspective, of course, but still. Just as the Shanghai Bund view has changed (the pictures are from 1990 to 2010) so have the participants, contents and business environment of my courses.

This is just about the 15th time I teach in China, all of it in cooperation with Fudan University, which gives me some cause to reflect on how teaching in China has changed – all seen from my rather narrow perspective, of course, but still. Just as the Shanghai Bund view has changed (the pictures are from 1990 to 2010) so have the participants, contents and business environment of my courses. The Table of Contents in the paper and PDF version of

The Table of Contents in the paper and PDF version of