The History of Software Engineering

an ACM webinar presentation by

ACM Fellow Grady Booch, Chief Scientist for Software Engineering, IBM Software

(PDF slides here.)

Note: These are notes taken while listening to this webinar. Errors, misunderstandings and misses aplenty…

(This is one of the perks of being a member of ACM – listening to legends of the industry talking about how it got started…)

Trust is fundamental – and we trust engineering because of licensing and certification. This is not true of software systems – and that leads us to software engineering. Checks and balances important – Hammurabi code of buildings, for instance. First licensed engineer was Charles Bellamy, in Wyoming, in 1907, largely because of former failures of bridges, boilers, dams, etc.

Systems engineering dates back to Bell labs, early 1940s, during WWII. In some states you can declare yourself a software engineer, in others licensing is required, perhaps because the industry is young. Computers were, in the beginning, human (mostly women). Stibitz coined digital around 1942, Tukey coined software in 1952. 1968-69 conference on software engineering coined the term, but CACM letter by Anthony Oettinger used the term in 1966, but the term was used before that (“systems software engineering”), most probably originated by Margaret Hamilton in 1963, working for Draper Labs.

Programming – art or science? Hopper, Dijkstra, Knuth, sees them as practical art, art, etc. Parnas distinguished between computer science and software engineering. Booch sees it as dealing with forces that are apparent when designing and building software systems. Good engineering based on discovery, invention, and implementation – and this has been the pattern of software engineering – dance between science and implementation.

Lovelace first programmer, algorithmic development. Boole and boolean algebra, implementing raw logic as “laws of thought”.

First computers were low cost assistants to astronomers, establishing rigorous processes for acting on data (Annie Cannon, Henrietta Leavitt.) Scaling of problems and automation towards the end of the 1800s – rows of (human) computers in a pipeline architecture. The Gilbreths created process charts (1921). Edith Clarke (1921) wrote about the process of programming. Mechanisation with punch cards (Gertrude Blanch, human computing, 1938; J Presper Eckert on punch car methods (1940), first methodology with pattern languages.

Digital methods coming – Stibitz, Von Neumann, Aitken, Goldstein, Grace Hopper with machine-independent programming in 1952, devising languages and independent algorithms. Colossus and Turing, Tommy Flowers on programmable computation, Dotthy du Boisson with workflow (primary operator of Colossus), Konrad Zuse on high order languages, first general purpose stored programs computer. ENIAC with plugboard programming, dominated by women, (Antonelli, Snyder, Spence, Teitelbaum, Wescoff). Towards the end of the war: Kilburn real-time (1948), Wilson and Gill subroutines (1949), Eckert and Mauchly with software as a thing of itself (1949). John Bacchus with imperative programming (Fortran, 1946), Goldstein and von Neumann flowcharts (1947). Commercial computers – Leo for a tea company in England. John Pinkerton creating operating system, Hoper with ALGOL and COBOL, reuse (Bener, Sammet). SAGE system important, command and control – Jay Forrester and Whirlwind 1951, Bob Evans (Sage, 1957), Strachey time sharing 1959, St Johnson with the first programming services company (1959).

Software crisis – not enough programmers around, machines more expensive than the humans, priesthood of programming, carry programs over and get results, batch. Fred Brooks on project management (1964), Constantin on modular programming (1968), Dijkstra on structured programming (1969). Formal systems (Hoare and Floyd) and provable programs; object orientation (Dahl and Nygaard, 1967). Main programming problem was complexity and productivity, hence software engineering (Margaret Hamilton) arguing that process should be managed.

Royce and the waterfall method (1970), Wirth on stepwise refinement, Parnas on information hiding, Liskov on abstract data types, Chen on entity-relationship modelling. First SW engineering methods: Ross, Constantine, Yourdon, Jackson, Demarco. Fagin on software inspection, Backus on functional programming, Lamport on distributed computing. Microcomputers made computing cheap – second generation of SW engineering: UML (Booch 1986), Rumbaugh, Jacobsen on use cases, standardization on UML in 1997, open source. Mellor, Yourdon, Worfs-Brock, Coad, Boehm, Basils, Cox, Mills, Humphrey (CMM), James Martin and John Zachman from the business side. Software engineering becomes a discipline with associations. Don Knuth (literate programming), Stallman on free software, Cooper on visual programming (visual basic).

Arpanet and Internet changed things again: Sutherland and SCRUM, Beck on eXtreme prorgamming, Fowler and refactoring, Royce on Rational Unified Process. Software architecture (Kruchten etc.), Reed Hastings (configuration management), Raymond on open source, Kaznik on outsourcing (first major contract between GE and India).

Mobile devices changed things again – Torvalds and git, Coplien and organiational patterns, Wing and computational thinking, Spolsky and stackoverflow, Robert Martin and clean code (2008). Consolidation into cloud: Shafer and Debois on devops (2008), context becoming important. Brad Cox and componentized structures, service-oriented architectures and APIs, Jeff Dean and platform computing, Jeff Bezos.

And here we are today: Ambient computing, systems are everywhere and surround us. Software-intensive systems are used all the time, trusted, and there we are. Computer science focused on physics and algorithms, software engineering on process, architecture, economics, organisation, HCI. SWEBOK first 2004, latest 2014, codification.

Mathematical -> Symbolic -> Personal -> Distributed & Connected -> Imagined Realities

Fundamentals -> Complexity -> HCI -> Scale -> Ethics and morals

Scale is important – risk and cost increases with size. Most SW development is like engineering a city, you have to change things in the presence of things that you can’t change and cannot change. AI changes things again – symbolic approaches and connectionist approaches, such as Deepmind. Still a lot we don’t know what to do – such as architecture for AI, little rigorous specification and testing. Orchestration of AI will change how we look at systems, teaching systems rather than programming them.

Fundamentals always apply: Abstraction, separation, responsibilities, simplicity. Process is iterative, incremental, continuous releases. Future: Orchestrating, architecture, edge/cloud, scale in the presence of untrusted components, dealing with the general product.

“Software is the invisible writing that whispers the stories of possibility to our hardware…” Software engineering allows us to build systems that are trusted.

Sources: https://twitter.com/Grady_Booch, https://computingthehumanexperience.com/

Eivind Grønlund, one of my students at the

Eivind Grønlund, one of my students at the  Neal Stephenson:

Neal Stephenson:  Tracy Kidder:

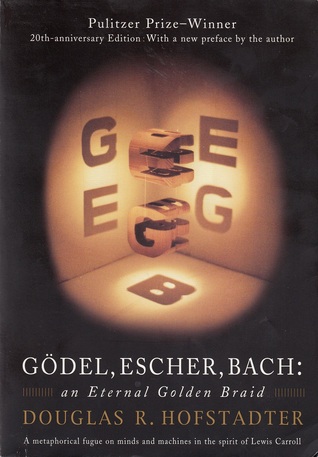

Tracy Kidder:  Douglas Hofstadter:

Douglas Hofstadter:  Tim O’Reilly:

Tim O’Reilly:

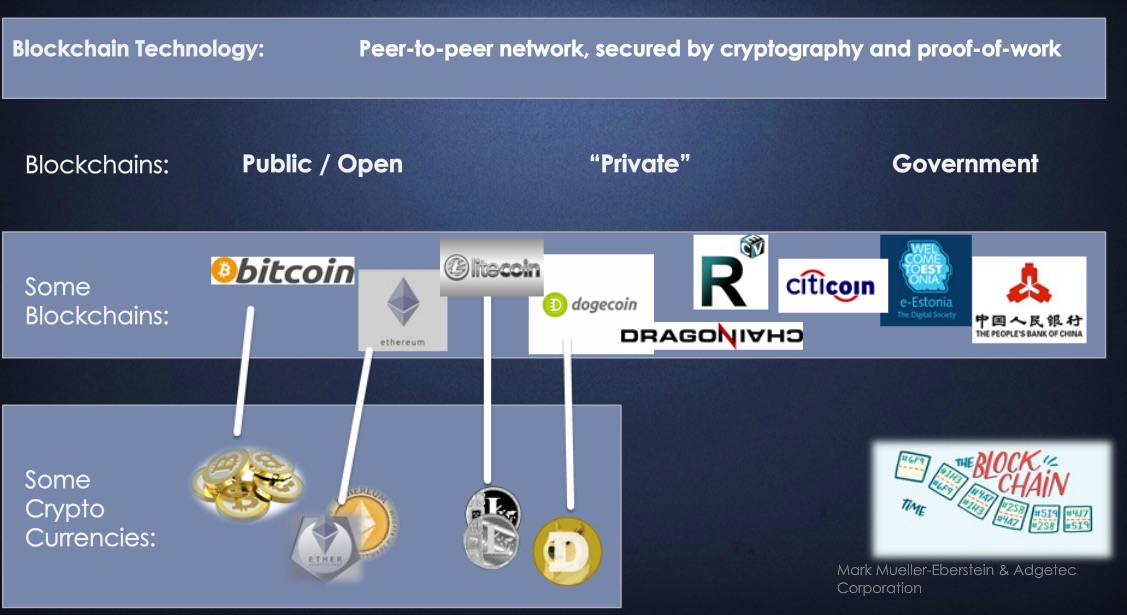

Data and data analytics is becoming more and more important for companies and organizations. Are you wondering what data and data science might do for your company? Welcome to a three-day ESP (Executive Short Program) called

Data and data analytics is becoming more and more important for companies and organizations. Are you wondering what data and data science might do for your company? Welcome to a three-day ESP (Executive Short Program) called  I just got the message that the new bachelor program

I just got the message that the new bachelor program

I have been asked to give a keynote speech at

I have been asked to give a keynote speech at